Otto von Bismarck of Prussia invented the KulturKamp (Culture War) that the Left has used against the Church

The Crown of France clearly did not realize that, in its successful push for the suppression of the Jesuit order, it had signed its own death warrant. Needless to say that the Jesuits would have been invaluable in engaging with the two forms of modernity that emerged during their suppression (which lasted between 1767 and 1814) — Populism and the Left.

France was an ideological cauldron. Henry IV after his “conversion” to Catholicism, had — like many monarchs — begun to wield a great deal of influence over the consecration of the Bishops in France. In 1604, Henry nominated Armand Jean du Plessis to become Bishop of Lucon. The Bishop soon became Cardinal Richelieu — controlling the apparatus of the French state and recalibrating French policy as Nationalist — and forging a historically unprecedented alliance with the Protestants and Turks (both historical enemies of France) against the Catholics in the 30 Years War. Without the support of France, the Reformation in Europe might be as archaic a memory as that of the Cathars of Southern France.

Additionally, under the influence of Henry, Calvinist influence began to swiftly permeate the upper levels of the Church in France. The Jansenist heresy was born — a sort of unforgiving Catholic-Calvinist hybrid portrayed by the character Javert in Les Miserables.

As France became more nationalist, the Church in France developed Gallicanism — the idea that the Church in France had special allegiance to the State to the detriment of its loyalty to the Pope. Jansenism and Gallicanism formed a putrid Church-state alliance that created resentment in some of the underclass Third Estate of France. Jesuit suppression decreased authentic Catholicism in France. In 1787, the Left took advantage — declaring religion was sectarian, dangerous, and in need of secular state management. In the French Revolution, Catholicism was banned by Robespierre and replaced by the atheistic Cult of Reason. A statue of the goddess Reason was built with a guillotine at her feet. Many heads were lost to her. When Robespierre realized his terrible mistake, he announced the state would have a Cult of the Supreme Being instead. But Robespierre had called forth a demon too hard to control and his own head was lost to the bloodthirsty Goddess of Reason.

Napoleon — after spreading a somewhat toned down version of the Left across Europe — got Pope Pius VII to sign the Concordat of 1801, which gave the State control of the Church in Europe and put priests on government payroll. This disastrous arrangement — whereby private citizens are coercively taxed to support the Church, which has an economically subservient arrangement with the State — is still ongoing in most of the countries that were once under the thumb of the short Corsican. Historically, State control of the Church weakens and erodes the faith of the laity — as evident in Europe.

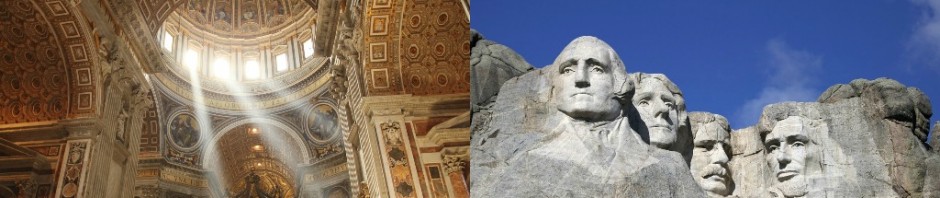

The Left gained increasing power in Europe. With the Church in Catholic Europe made more impotent by its reliance on the state, Otto von Bismarck of majority-Protestant Prussia declared a Kulturkampf (Culture War) against the Catholic Church through a secularist State war on the Church. By World War II, France — influenced by its Leftist roots — and Marxist Socialists in Russia were waging a war against Nazi Socialists in Germany and Fascist Socialists in Italy. The Left’s ascent in Europe was so thorough that France was one of the least Leftist states on the Continent (not saying much).

After the Jesuit suppression, the Church relied primarily on the Parish Priest as its primary means of operation. The Church was understandably fiercely opposed to the anti-Catholic modernity represented by the Left. The Left launched an attempt to influence the Church that it needed to “modernize” its moral doctrines. In 1888, Leo XIII condemned the Left’s conflation of license and liberty in the Encyclical Libertas. Leo XIII condemned Americanism in Testem Benevolentiae Nostrae in 1910. In 1910, Pope Pius X instituted an Oath Against Modernism. All three documents condemned any attempt to institute progressive doctrine repudiation and modern doctrinal updates within the Church. The Parish provided a fortress that allowed the Church to flee Leftist persecution in Europe and (a far milder) anti-Catholic Protestant persecution in the United States. The Parish priest celebrated the Latin Mass and built Catholic schools and Catholic communities that served as a harbor to a Church rocked by the Leftist ascendancy in the governments of Europe.

An estimated two-thirds of all Catholic martyrs in history died in the 20th century — mostly at the bloody hands of Leftists. The most ruthless periods of Catholic persecution occurred in the Parochial era — from the French Revolution to Nazism to Communism.

Until the Church formed a Catholic-Populist alliance in 1965 that shook the Left to its core.