The 30 Years War saw an alliance of French Nationalists, Turkish Islamists, and Protestants vs. Catholics

The kindling wood of the Protestant Reformations (yes, there were two Reformations) were the actions of Catholic elitism in Southern France and Prussia.

The French Crown (not the Church) burned many Cathars at the stake for heresy. There is no question that committed Cathars were bent on waging war on the state. Therefore, the same men could have been executed for insurrection. However, the Dominican-led Inquisition allowed the Catholic monarch to execute citizens for the sake of peace wrapped in the language of correcting heresy. This effectively allowed the state to use the Church for public relations purposes — an inappropriate Church subservience to the state. It did not help when the French Crown managed to keep the Popes in Avignon for 67 years.

The Teutonic Knights had the opposite problem. They had established what they called a monastic state in Prussia. Which meant that the Knights ruled the affairs of the pagan clan chiefs for their own good. The conversions to Catholicism were bitter and resentful.

In 1517, Martin Luther wrote the 95 theses and began to develop his own doctrines. He believed that faith and reason are inherently in conflict. The predestined saved should “sin boldly” to internalize how much they needed Jesus. He believed that the Church should be controlled by the state. State control of the Church was appealing to the Prussian nobles that had long operated under Church control of the state. In 1525, the Grand Master of the Knights converted the state to Lutheranism and became Duke Albert of Prussia. The nobles seized the wealth of the Church and ceased paying the tithe or funding charity. A peasant rebellion arose but Albert executed their leaders in an alleged peace negotiation.

John Calvin envisioned a very different Reformation. He believed the Church should control the state. He believed in a state where essentially all immoral actions were illegal. Some historians have described Puritans as the inventors of the police state. John Calvin also believed in double predestination — that God creates some people for the purpose of sending them to Heaven and others for the purpose of damning them to Hell. He believed that God showers worldly blessings (like wealth) on the predestined. His particular vision of Christianity was — needless to say — more popular with nobles and merchants than common people. His faith took hold in Southern France where memories of the Inquisition still rankled. From 1562 – 1598, Calvinist Hugenots (mostly nobles from the south) fought the Catholic League (mostly commoners from Paris). In 1598, Henry IV (a Huguenot who had “converted” to Catholicism to inheret the throne) issued the Edict of Nantes, which declared religious liberty and recalibrated French policy as Nationalist rather than Catholic.

England converted to Anglicanism due to Henry VIII’s desire to marry Anne Boelyn. In 1536, Henry proclaimed the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The outraged populace rose up under the banner of the Five Wounds of Christ and demanded Henry VIII restore the Catholic faith in England. Henry VIII promised to do so. When the peasant army disbanded, Henry VIII assassinated their leaders. England has been Anglican ever since.

Protestantism had immense appeal to nobles, merchants, and kings. It tended to empower the elites at the immediate expense of the Church and the commoners as well as the long-term expense (although this was not immediately evident) of the king. It was not popular with the populace of Europe. The phrase “Sola Scriptura” sounded elitist to the mostly illiterate masses who could effectively identify with the Catholic sacraments. As it spread across Europe, one thing stopped Protestantism in its tracks: the Society of Jesus. Saint Ignatius’ Jesuits had been recognized as a priesthood directly loyal to the Pope in 1540.

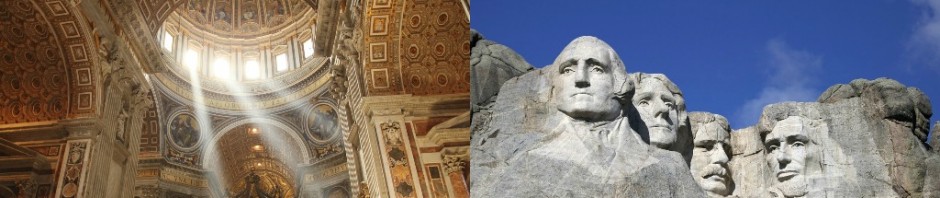

The Jesuits were everywhere. They revitalized science and art in the Catholic states untouched by the Reformation — Italy, Spain, and the Holy Roman Empire (Austria). They built Universities, Hospitals, and Charities. They plunged undercover in Protestant strongholds like England and Prussia to illegally provide the Sacraments to the Catholic populace. They led a spiritual renewal. They were martyred in immense numbers. They were educated. They debated. They were utterly unrelenting in their advocacy for the Faith. They provided counsel and spiritual direction to Catholic Kings and Bishops. They strategically attempted to outmaneuver allied Protestant, Islamist, and Nationalist powers from conquering Rome. They were unwaveringly loyal to the Pope in an age when many were deserting him. They halted the spread of Protestantism in Europe. And once the Age of Exploration began, they spread Catholicism to Africa, Asia, Australia, and the Americas.

Initially, Protestants believed that a noble-centric conversion could sweep across Europe. When that failed due to the Jesuits, they decided to attempt a trial of arms.

A Lutheran alliance of Prussia, Saxony, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden joined with Anglican England, Nationalist France, the Reformed Netherlands, and the Islamist Turkish Empire — which had conquered Constantinople and renamed it Istanbul — to fight the Catholics. The alliance was geared towards defeating the Catholic Holy Roman Empire, Catholic Spain, and the Catholic city-states of Italy, and ultimately capturing Rome.

The 30-years war was one of the largest and bloodiest wars ever fought. A stalemate ultimately ended in the Peace of Westphalia — a peace that was in some ways even worse than war. Westphalia abolished religious liberty in both the Catholic and Protestant states (except France) and declared that citizens had to share the religion of the Monarch. The disregarded Jesuits believed that such a peace was even worse than continuing war.

The Protestants and Catholics both erected brutal Inquisitions to enforce this provision. This created a Church-state alliance bitterly resented by the populace and opened the doorway for the rise of the Left. The rise of the Left was radically hastened by the papal suppression of the Jesuit order (under political pressure from France) in 1767.