The Walls of Rome Were Breached by the Italian Army in 1861

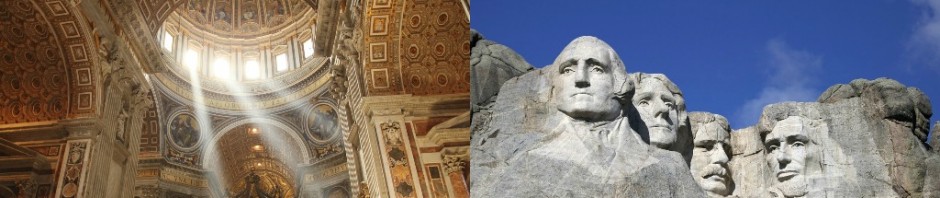

On September 20 of 1870, the Aurelian Walls in Rome were breached by heavy cannon fire from an Italian Army loyal to King Victor Emmanuel II. All in a moment, the radically outnumbered Swiss Guards and papal military volunteers were overwhelmed, the Risorgimento uniting Italy into one nation was completed, the First Vatican Council was effectively ended, Pope Pius IX was made “prisoner in the Vatican,” and the papacy lost its temporal power which it had wielded since the Crowning of Pepin in 752.

Commenting on this turn of events, Cambridge History Professor Lord Acton gave a speech describing his grief at seeing the defeat of the papacy. However, his speech was full of encouragement to Catholics whose faith in Providence was shaken. Lord Acton argued that the Papal monarchy operated in Rome had become a liability to the propagation of the Faith and that Catholicism and the papacy would flourish in its absence.

Lord Acton had been one of the earliest and most vocal advocates of the compatibility of democracy and Catholicism. Lord Acton believed that the Catholic teachings on the dignity of the human person, the natural order, and the natural law had created a fertile field in which natural rights philosophy was bound to emerge. In spite of the fact that John Locke had been the true founder of liberalism (a term whose meaning has changed so much in modern parlance that populism is a more accurate description of this phenomenon), Lord Acton still regarded liberalism as born out of the Catholic intellectual tradition.

In the speech, Lord Acton offers a birds eye view of the papal throne-and-altar politics which he believed had hampered the Catholic development of natural rights theory. He made the case that the papacy had developed a level of political power that had caused its foreign policy decisions to have far-reaching resentment in certain developing nation-states of Europe even before the Reformation. The Reformation allowed for a great expansion of power by Kings and nobles at the expense of the Catholic Church and the populace — particularly the poor who most relied on Catholic Guilds, Monasteries, Hospitals, and Schools. During the Reformation, the idea of the Divine Right of Kings was developed and was later famously endorsed by Martin Luther in his elitist tract Against the Murderous, Thieving Horde of Peasants written during the German Peasants War.

The Protestant princes — after putting down the peasants — fought against the Hapsburgs in the Catholic Empires of Austria and Spain (with some help from the treacherous Cardinal Richelieu of France and the Islamist leaders of the Ottoman Empire) in the grueling 30-years war. The out-manned Hapsburgs agreed to the Peace of Westphalia.

Innocent X strongly objected to the Peace of Westphalia, which endorsed the Divine Right of Kings and announced that the prince had the authority to impose his religion on the populace regardless of their desires. This led to Protestant and Catholic Inquisition Courts (both of which Lord Acton opposed) which were set up to ensure that the populace conformed to the religion of the monarch. In Protestant countries, the subjection of religion to the control of the state led to precipitous theological and participatory decline as the populace sensed that religion was no longer serving a divine end but a political end.

Meanwhile, the papacy’s political interests became dire as militant Protestantism and militant atheism advanced. For example, political considerations in direct violation of pastoral considerations allowed the French monarchs to successfully pressure the papacy to suppress the Jesuit order when their renowned intellects were most needed (during the eve of the French Revolution). Furthermore, the papal monarchy had a political imperative of maintaining its diplomatic friendships with the Catholic emperors of France and Austria and the Catholic monarchs of Spain, which prevented the papacy from proper pastoral, intellectual, and theological engagement with ascendent democratic principles.

Lord Acton argued that the end of the temporal power, provided that the papacy would be granted sovereign authority over a small piece of land would have the following benefits:

1) The papacy would engage without political reservations with the new democratic principles that were rising to power throughout the world and join the debate as the pre-eminent champion of human rights in a democratic world.

2) It would end the Protestant and atheist propoganda that Catholicism — as evidenced by the papal monarchy itself — was incompatible with democratic human rights.

3) It would allow the papacy to shift its focus to Christ’s mercy rather than secular justice.

4) It would allow the Pope to develop (counter-intuitively) more political influence — focusing exclusively on the Catholic religion that shapes culture that in turn shapes politics.

Lord Acton revealed these insights in the mid 18th Century. Like many of the greatest historians, he was blessed with great foresight.

Joseph Stalin, on the other hand, was not so blessed. In 1935, responding to a warning against his contempt of the papacy, he sneered, “How many divisions has the Pope?”

In light of the largely John Paul the Great-inspired fall of the Berlin Wall and all that Stalin had hoped to achieve, the answer to this question has proven to be, “Enough.”