Claims of contradiction on Catholic teaching on religious liberty were promoted by SSPX

Archbishop Lefebvre, the founder of the Society of Saint Pius X, was never a fan of the Second Vatican Council — even while he was still in communion with the Church.

Failing to make distinctions between the condemned Modernism of the Left condemned by the Church (the idea that truths change as society evolves — often violently — towards post-suffering utopia) and the Modernity of Populism (which replaced Natural Law and Revealed Law with Natural Law and Natural Rights), the the Archbishop condemned the ideological alliance between Catholicism and Populism. In 1988, he ordained four Bishops without papal approval — thus launching the Society of Saint Pius X into schism.

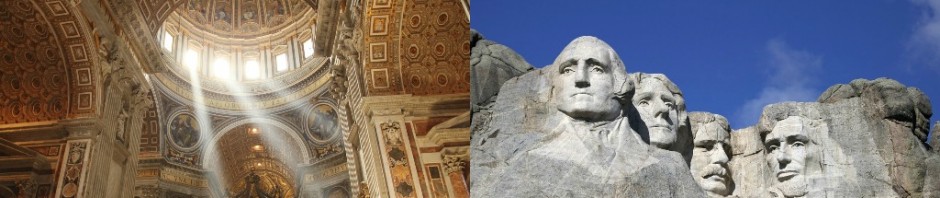

That same year, he published a blistering critique of Vatican II in They Have Uncrowned Him: From Liberalism to Apostacy: The Conciliar Tragedy. In it, the Archbishop charged that the Church had succumbed to Modernism in endorsing the moral viability of a nation governed by Populism, which is the guiding principle the United States, rather than by the principle of Christianity, which was the guiding principle of Christendom.

The Council document that does the most heavy lifting on this issue is Dignatitis Humanae (The Declaration on Religious Freedom). Archbishop Lefebvre’s critique justified two conclusions. It justified the newly schismatic SSPX for breaking off from the Church since it seemed that (contrary to the promises of Christ) the Gates of Hell had gotten the better of the Church at last. It also justified self-identified “Catholic” Modernists (although Modernism is in fact a heresy or theological error). Modernists claimed: “The Church does change its position on Truth and therefore truth does change. Who knows what will be next? Perhaps some of our favorite targets — contraception and women’s ordination.”

The Modernists and SSPX are both radically wrong, of course.

A central question arises:

Can the Church endorse as morally acceptable as governing principles both Populism and Christianity without contradicting itself? Can the Church give the impramatur of moral acceptability both to Historic Christendom and the United States of America?

The answer is simple: The Church can do so and it has done so.

However, in order to take their argument seriously, we must examine the seemingly stark differences in the early papal encyclicals and the later papal encyclicals. The key encyclical that was later the springboard for all subsequent commentary is Mirari Vos (On Liberalism and Religious Indifferentism) — an 1832 Encyclical promulgated by Pope Gregory XVI:

“Now We consider another abundant source of the evils with which the Church is afflicted at present: indifferentism. This perverse opinion is spread on all sides by the fraud of the wicked who claim thatit is possible to obtain the eternal salvation of the soul by the profession of any kind of religion, as long as morality is maintained.”

“This shameful font of indifferentism gives rise to that absurd and erroneous proposition which claims that liberty of conscience must be maintained for everyone.”

“Nor can We predict happier times for religion and government from the plans of those who desire vehemently to separate the Church from the state, and to break the mutual concord between temporal authority and the priesthood. It is certain that that concord which always was favorable and beneficial for the sacred and the civil order is feared by the shameless lovers of liberty.”

This article postdates the Peace of Westphalia that ended the Thirty Years War. The only country openly trumpeting its freedom of religion was France. France happened to be the Catholic nation that adopted Ethnic Nationalism as its guiding policy in place of Christendom. Ethnic Nationalism — inherently warlike and self-interested — has never been considered morally acceptable according to Catholic teaching. Furthermore, the Left had laid hold of France with its slogan of Liberty (with an endorsement of a post-moral license), Fraternity (ethnic nationalism), and Equality (utopian equality of result).

Indifferentism has always been a serious theological error within Catholic thought. There is no question that French Policy — represented by the slogan — had enormous levels of indifferentism. Although France had a state-managed Catholic Church installed by Napoleon, the Church was subordinate to the state in every way. Amoral license, ethnic nationalism, and worldly utopia are all in direct opposition to Catholic teaching.

None of this applied to Populism.

Populism did not separate Church and State ideologically as the Left does. The Declaration of Independence cites the justification for the state in the “Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God.” They operate in a separate fashion in practice. However, there is no promotion of the idea that the state has a different ideological source from the Church.

Furthermore, the Founders considered there to be a stark difference between what they called license (amoral freedom) and Liberty (the freedom to operate within the Natural Law). The Founders did not believe in a freedom of conscience that trumped Natural Law. In a correct application of founding principles, Utah was not admitted into the Union until it first abolished polygamy. Mormon religious conviction was trumped by Natural Law.

Finally, Populism respects the Church and calls for its urgent application. George Washington addresses this in his Farewell Address at length. Here is a snippet:

“Of all the dispositions and habits, which lead to political prosperity, Religion, and Morality are indispensable supports … Whatever may be conceded to the influence of refined education on minds of peculiar structure—reason and experience both forbid us to expect, that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.”

The Church has always and will always endorse Christianity as a governing principle — as was the case with Christendom. However, without ever contradicting itself, in 1965 it has also now endorsed Populism as an alternate morally sound governing principle.

The Church never uncrowned Christ, as Lefebvre maintained. It left Christ with his crown intact over Christendom. But it also prepared for a New Evangelization in the Populist era.