Anthony of the Desert

The interesting thing about the history of Catholicism, as GK Chesterton so wisely pointed out, is the Catholic Church in history tended to virtually die over and over again. In the early Christian Church, its Popes and Bishops were repeatedly killed. When it died, the conventional wisdom tended to build a tomb for it, stick a rock on top, and hope that no more trouble would come of it. Then, it rose again. And again.

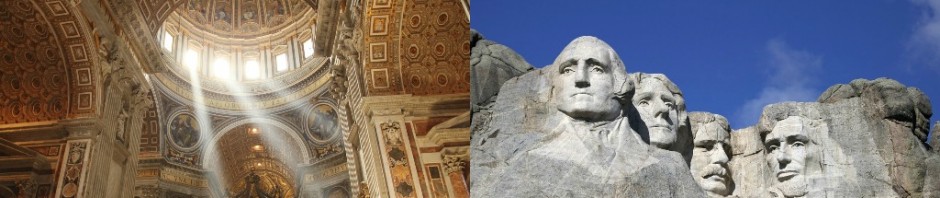

In 312, Constantine the Great saw a Christian vision promising him victory in the Battle of Milvian Bridge, a battle for control of the Empire. Upon his victory and rise to Emperor, he decided that he would need to do some pretty ruthless things for the sake of Christianity, so he held off on Baptism. However, in 313, he released the Edict of Milan, which proclaimed religious liberty in the Empire and spelled an end to Christian persecution. In 330, he moved the capital of the Roman Empire to Byzantium, which was forthwith renamed Constantinople. He was baptized by a heretical Arian bishop and died in 337.

His reign changed the course of history.

Christianity instantly became mainstream. The elites at the court began to convert — some genuinely and some not. The Emperor began to have enormous influence over the appointment of Bishops — particularly in the Greek speaking East of the Empire, which eventually came to be called the Byzantine Empire. However, the elites were not entirely comfortable with the new religion. Certainly, it was fashionable. But wasn’t it just a little extreme to say that Jesus, a carpenter’s son, was one person in the Triune godhead? Fortunately, a priest named Arius began to teach that Jesus was the Son of God but not equal with the Father. Of course not! The Arian heresy became quickly ascendant. Soon, most Bishops (most of whom were in the East) and most of the Emperors were Arians. The Popes and their allies (such as Athanasius) waged ceaseless war against Arianism.

However, not everyone thought that the new high levels of cooperation between so many Bishops and the Empire were a good thing. One such man was the hermit Anthony of the Desert. He believed that since martyrdom had become defunct in 313 (two years after he himself had aggressively put himself in a near occasion of martyrdom), Christians had to die to themselves in another way. He began the movement towards Eastern Christian monasticism. Under his tutelage, monks (and nuns separately) began to build communities with each other. Most monks were not priests but a few priests ministered to each monastery. They prayed and worked constantly to achieve sanctification. Monasteries (over the next several centuries) invented hospitals, community schools, and charities for the poor as their method of service. Their evangelization was part of a populist campaign against Arianism. They were critical to protecting the true faith in the East.

Benedict of Nursia two centuries later introduced the Rule of Saint Benedict to the West. In the West, the monastery served a different purpose. Taking advantage of the power vacuum opened up in Rome by the removal of the Capital to Constantinople, waves of Germanic people who had been part of the Roman Army advanced into Rome. Most of these had become Arian under the influence of the Roman establishment. Alaric the Goth (an Arian) conquered Rome in 410. The monks of the West sought sanctification in prayer and work. However, the Middle Ages were a ceaseless period of invasions — the Saxons, the Goths, the Vandals, the Huns, the Vikings, the Magyars, the Moors, and others — and monasteries offered the communities built around them the service of some protection. The monasteries in the West preserved the Bible as well as other precious documents to preserve the learning that would be critical to the next wave of evangelization.

The western Church was repeatedly almost obliterated by barbarian hordes. The eastern Church was repeatedly almost co-opted by Arianism — the greatest heresy in history.

Through it all, the monks (and nuns) chanted, worked, prayed, built strong walls, served as a rock in the midst of a historical tempest, held fast to the true faith, preserved the truths of the early Church and the learning of antiquity, practiced charity to the poor, educated the people, scoffed at heretical bishops, and served as the rock of the Church.

The monks perfected a new form of martyrdom — death to self.

And the Church held strong.