Joseph de Maistre was a Leading Ultramontanist Theorist

In Against the Murderous, Thieving Horde of Peasants, Martin Luther made the revolutionary set of statements that Romans 13: 1 – 7 has inherent within it the idea that Political Might Makes Right: “For a prince and lord must remember in this case that he is God’s minister and the servant of his wrath (Romans XIII), to whom the Sword is committed … Here, then, there is no time for sleeping; no time for patience and mercy.”

Martin Luther makes the cardinal Biblical interpretation error of ignoring those to whom the statement is addressed. Paul is telling the Christians to obey civil law when it does not conflict with divine law and urging the Christians to view the civil law as legitimate even though it does not come from Christ. Paul is endorsing good citizenship. Martin Luther takes the comment and applies it to the rulers, assuming that they have divine authorization to exercise their power devoid of mercy (rather against Christian orthodoxy). In the tract, Luther even declares that for civil rulers, the ends justifies the means — a direct violation of the dignity of the human person and basic natural law theory.

Luther took his logic to its natural extension, arguing that the princes and the nobles ought to control the Church. Luther found many willing adherents to this idea among the nobles of Europe — from the princes of Germany to the nobles in England to the Huguenots in France. Throughout Europe, this caused a chain reaction:

1) Nobles ceased paying the tithe to the Catholic Church that was typically used for Church administration and charitable activity.

2) Nobles began to be able to lend with more usury, a practice that had in Medieval times been reserved to Jewish merchants.

3) Nobles seized the wealth of monasteries, guilds, and churches, gaining access to the Church’s more liquid assets.

4) Nobles throughout Europe began to grow much more wealthy and more powerful than they had been, both in relation the commoners and to the King.

Predictably, the French King, concerned that his own nobles — particularly the Huguenots — would buy into this theory, began to patronize theorists who took the Political Might Makes Right and converted it into the more narrowly-defined Divine Right of Kings. The French Crown smiled particularly on Jean Bodin and Jacques-Benigne Bossuet, the leading Divine Right of Kings theorists. Once the French Crown put down the Huguenot uprisings (led by Nobles quite interested in Luther’s theory), Cardinal Richelieu put the theory into practice, immensely centralizing power into royal hands by his crafty statesmanship. While the nobles grew stronger and the Kings grow weaker in the Protestant countries, in the Catholic countries the Kings grew stronger in relation to the nobles and to the papacy.

The papacy had long been the dominant political power player in Europe and it was alarmed at its growing political weakness. The papacy no longer had the strength to shape the secular policy of Europe by traditional political methods (allies, diplomacy, and might). The powerful Jesuit order, who swore an oath of personal loyalty to the Pope, mostly began to believe that the solution was for the papacy to issue an ultramontane declaration. Such a declaration would announce that papal foreign policy was essentially infallible. To be a Catholic, in other words, would be to have political allegiance to the Pope.

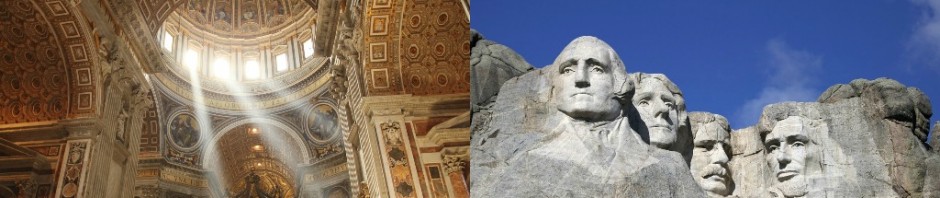

In order to issue such a declaration, there needed to be a Council. The Jesuit push for an ultramontane-focused Council was curtailed by their suppression from 1767 to 1815 under pressure from indignant European monarchs. In 1819, philosopher Joseph de Maistre published a well-received tract arguing for an ultromontane decree. The ultramontanes were finally able to convene the desired Council — the First Vatican Council — in 1868.

At the Council, the ultramontane goal was to make two declarations of papal infallibility — one on faith and morals and one on secular affairs. However, Blessed John Henry Newman and Lord Acton led the populist wing in the Council and, though badly outnumbered, they were fierce opponents of the ultromontanes at the Council. The populists attempted to prevent a vote on papal infallibility — desiring to delay in the face of overwhelming ultromontane strength. Finally, Cardinal Newman successfully convinced the Council to adopt a very narrow definition of papal infallibility (the ex cathedra definition). When the ultramontanes began to push for a vote on papal infallibility in matters relating to secular affairs, the walls of Rome were breached and Vatican I was roughly ended.

The Lord works in mysterious ways and perhaps Vatican I was ended in the nick of time.

The ultramontane wing of the Church never recovered and, in Vatican II, were outmaneuvered by the populists in a Council emphasizing the universal call to holiness.