Archbishop Dolan leads the American Catholic Church with Tools Bequeathed by Leo XIII

Leo XIII wrote five great encyclicals that have defined the relationship between the three great institutions that define society — family, government, and Church — Arcanum (On Christian Marriage), Diuturnum (On the Origin of Civil Power), Immortale Dei (On the Christian Constitution of States), Libertas (On the Nature of Human Liberty), and Sapientiae Christanae (On Christians as Citizens).

Leo XIII believed that marriages were the directly under the jurisdiction of the Church, without whose grace the sacrament would fail and be left unprotected:

“Lastly, with such foresight of legislation has the Church guarded its divine institution that no one who thinks rightfully of these matters can fail to see how, with regard to marriage, she is the best guardian and defender of the human race; and how, withal, her wisdom has come forth victorious from the lapse of years, from the assaults of men, and from the countless changes of public events” (Arcanum).

Leo believed that the family was the bedrock of all society:

The family may be regarded as the cradle of civil society, and it is in great measure within the circle of family life that the destiny of the States is fostered. Whence it is that they who would break away from Christian discipline are working to corrupt family life, and to destroy it utterly, root and branch” (Sapientiae Christianae).

Leo also believed in a Church and state mutually respecting harmony:

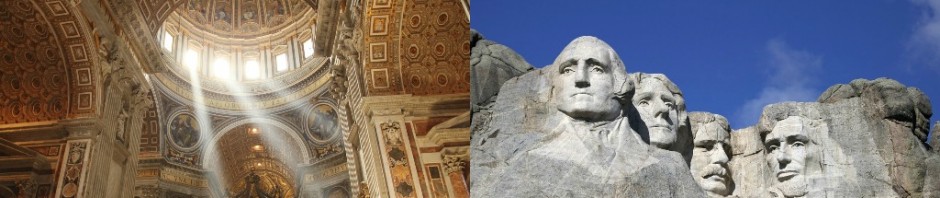

“The Almighty, therefore, has given the charge of the human race to two powers, the ecclesiastical and the civil, the one being set over divine, and the other over human, things. There must, accordingly, exist between these two powers a certain orderly connection, which may be compared to the union of the soul and body in man … Whatever, therefore in things human is of a sacred character, whatever belongs either of its own nature or by reason of the end to which it is referred, to the salvation of souls, or to the worship of God, is subject to the power and judgment of the Church. Whatever is to be ranged under the civil and political order is rightly subject to the civil authority. Jesus Christ has Himself given command that what is Caesar’s is to be rendered to Caesar, and that what belongs to God is to be rendered to God” (Immortale Dei).

Leo took the populist view (greatly diverging from his highly political and influence-broker predecessors) that the Church should avoid nitty-gritty politics:

“And since she not only is a perfect society in herself, but superior to every other society of human growth, she resolutely refuses, promoted alike by right and by duty, to link herself to any mere party and to subject herself to the fleeting exigencies of politics” (Sapientiae Christianae).

However, Leo made the point that free will is only free when a human being rationally assesses two divergent courses of action with reason. Without reason, man can have no more basis than animals:

“In other words, the good wished by the will is necessarily good in so far as it is known by the intellect; and this the more, because in all voluntary acts choice is subsequent to a judgment upon the truth of the good presented, declaring to which good preference should be given” (Libertas).

One of the main ways that reason is wounded is by the indulgence of license towards an evil end. This allows passions to cloud the intellect. Men indulging in license and rationally blinded become enslaved to sin and addiction and thus become less free:

“The will also simply, because of its dependence on the reason, no sooner desires anything contrary thereto than it abuses its freedom of choice and corrupts its very essence. Thus it is that the infinitely perfect God, although supremely free, because of the supremacy of His intellect and of His essential goodness, nevertheless cannot choose evil; neither can the angels and saints, who enjoy the beatific vision” (Libertas).

Thus, the preservation of liberty requires the avoidance of moral degeneracy and license. Here, Leo argues, the state relies on the Church to keep men free. He points out the hypocrisy of the Left, which under the banner of liberty but often attempts to suppress the Church, the true champion of liberty, in the name of freedom:

“And because the Church, the pillar and ground of truth, and the unerring teacher of morals, is forced utterly to reprobate and condemn tolerance of such an abandoned and criminal character, they calumniate her as being wanting in patience and gentleness, and thus fail to see that, in so doing, they impute to her as a fault what is in reality a matter for commendation. But, in spite of all this show of tolerance, it very often happens that, while they profess themselves ready to lavish liberty on all in the greatest profusion, they are utterly intolerant toward the Catholic Church, by refusing to allow her the liberty of being herself free” (Libertas).

He argues that the state is therefore dependent on the Church to maintain true ordered liberty. As a result, in the emerging democratic world that Leo XIII dwelt in, Catholics had much to offer the state that serve the state that are the hallmarks of the Catholic Church in America and throughout the democratic world:

1) Defense of liberty and maintenance of social order (American founders believed that a free society had to be a moral society): “The duties enjoined are incumbent on the same persons, as already stated, and between them there exists neither contradiction nor confusion; for some of these duties have relation to the prosperity of the State, others refer to the general good of the Church, and both have as their object to train men to perfection” (Sapientiae Christianae).

2) Charity (Catholic Charities, Catholic Hospital systems, etc.): “It is, however, urgent before all, that charity, which is the main foundation of the Christian life, and apart from which the other virtues exist not or remain barren, should be quickened and maintained” (Sapientiae Christianae).

3) Education (Catholic parochial system and college system): “Where the right education of youth is concerned, no amount of trouble or labor can be undertaken, how great soever, but that even greater still may not be called for. In this regard, indeed, there are to be found in many countries Catholics worthy of general admiration, who incur considerable outlay and bestow much zeal in founding schools for the education of youth” (Sapientiae Christianae).

4) Beneficial political advocacy (State Catholic Conferences, USCCB): “Whence it is clear that, in addition to the complete accordance of thought and deed, the faithful should follow the practical political wisdom of the ecclesiastical authority” (Sapientiae Christianae).”

5) Evangelization to multiply these great effects: (EWTN, Catholic Answers, FOCUS, Ave Maria Radio): “So soon as Catholic truth is apprehended by a simple and unprejudiced soul, reason yields assent” (Sapientiae Christianae).

This new vibrant vision of a populist Catholicism has helped carry the US to the vanguard of the movement to return America back to her founding principles.